He is one of the best rulers ever to rule Europe, most of Italy and many Gallic and Germanic tribes.

Charlemagne - Father of the Holy Roman Empire Documentary

Its very interesting that this great man was born in such backwater place. Also, he was born into the period which was just few generations far from the fall of Roman Empire. I would like to see how these people lived there because I can imagine that the south was pretty much still advanced and the tribes who were originally attacking Roman Empire were still finding the way how things are working.

Dave Stotts: Charlemagne's Impact on the Course of Christian History | The State of Faith | TBN

On TBN's special, State of Faith: Northern Europe, Drive Thru History's Dave Stotts explores Charlemagne's impact on the course of Christian history in Northern Europe.

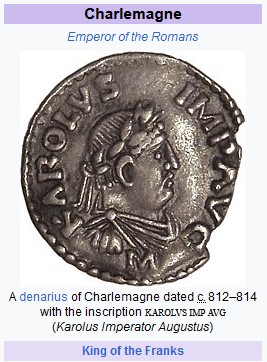

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Charlemagne (/ˈʃɑːrləmeɪn, ˌʃɑːrləˈmeɪn/ SHAR-lə-mayn, -MAYN) or Charles the Great (Latin: Carolus Magnus, Frankish: Karl;[3] 2 April 747[a] – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and was crowned as the Emperor of the Romans by the Papacy in 800. Charlemagne succeeded in uniting the majority of western and central Europe and was the first recognized emperor to rule from western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier.[4] The expanded Frankish state that Charlemagne founded was the Carolingian Empire, which is considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire. He was canonized by Antipope Paschal III—an act later treated as invalid—and he is now regarded by some as beatified (which is a step on the path to sainthood) in the Catholic Church.

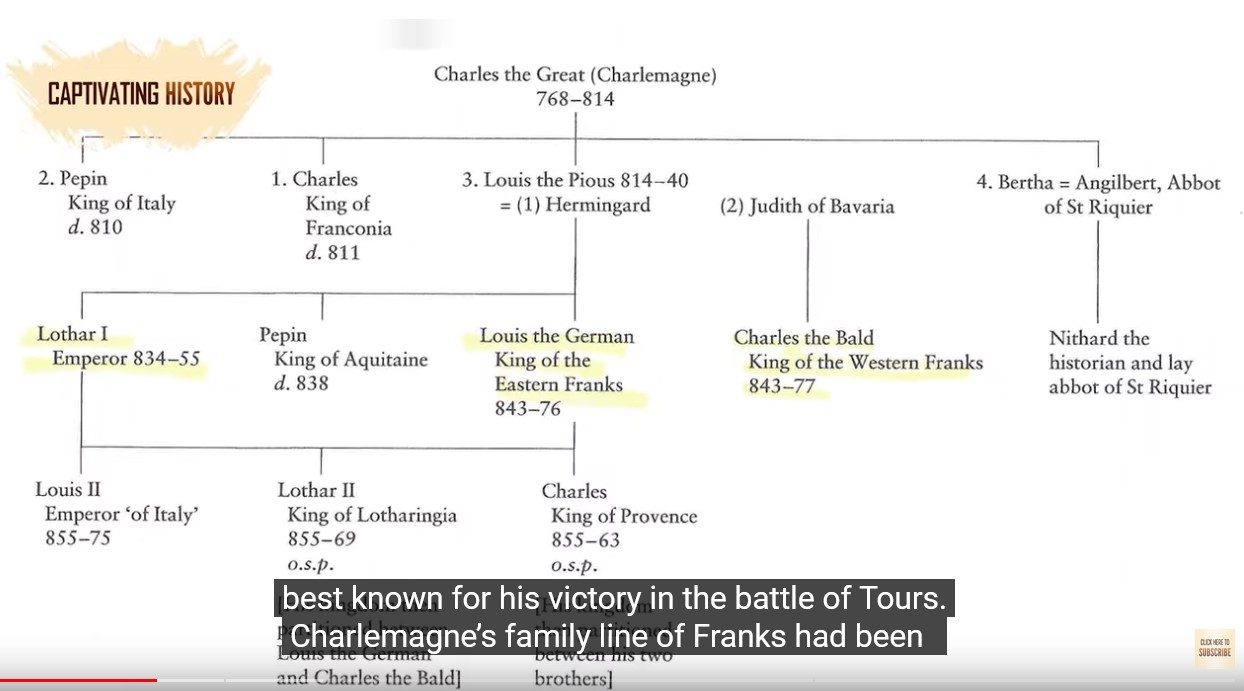

Charlemagne was the eldest son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon. He was born before their canonical marriage.[5] He became king of the Franks in 768 following his father's death, and was initially co-ruler with his brother Carloman I until the latter's death in 771.[6] As sole ruler, he continued his father's policy towards the protection of the papacy and became its sole defender, removing the Lombards from power in northern Italy and leading an incursion into Muslim Spain. He also campaigned against the Saxons to his east, Christianizing them (upon penalty of death) which led to events such as the Massacre of Verden. He reached the height of his power in 800 when he was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day at Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Charlemagne has been called the "Father of Europe" (Pater Europae),[7] as he united most of Western Europe for the first time since the classical era of the Roman Empire, as well as uniting parts of Europe that had never been under Frankish or Roman rule. His reign spurred the Carolingian Renaissance, a period of energetic cultural and intellectual activity within the Western Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church viewed Charlemagne less favourably, due to his support of the filioque and the Pope's preference of him as emperor over the Byzantine Empire's first female monarch, Irene of Athens. These and other disputes led to the eventual split of Rome and Constantinople in the Great Schism of 1054.[8][b]

Charlemagne died in 814 after contracting an infectious lung disease.[9] He was laid to rest in the Aachen Cathedral, in his imperial capital city of Aachen. He married at least four times,[10][2] and three of his legitimate sons lived to adulthood. Only the youngest of them, Louis the Pious, survived to succeed him. Charlemagne is a direct ancestor of many of Europe's royal houses, including the Capetian dynasty,[c] the Ottonian dynasty,[d] the House of Luxembourg,[e] the House of Ivrea[f] and the House of Habsburg.

Charlemagne: How He Changed History Forever

Warrior. Ruler. Patron of the arts and language. Terrorist. Brutal oppressor. Protector of the good. Guardian of Christendom. Father of Europe. There are so many different ways in which Charlemagne can be described, and yet the man himself is often seen as an enigma. Depending on the viewpoint of history, he could have been either a monster or a guardian angel. Yet, as with most men, the truth lies somewhere in between. The truth is that he was human.

Introduction

Although missionaries like Patrick and Augustine had made Christianity hugely successful in the British Isles, there was really only one tribe in the whole of mainland Europe who were mainstream Christians — the Franks, whose King had converted in 496. The others were all pagans or Arians.

All this changed when Charles the Great, or “Charlemagne” became King of the Franks, ruling from 771 to 814. He was a great military conqueror, and channeled this talent into the service of the church, for in taking over most of Western Europe and a fair bit of the east, he used military force to compel all his subject peoples to become Christian. He also sponsored more subtle missionary efforts, and encouraged the spread of Benedictine monasteries, and especially the copying of theological manuscripts.

The Pope crowned him Roman Emperor in 800, centuries after the ancient Roman Empire had collapsed in Europe — a move which infuriated the Eastern Emperor who still claimed to rule both east and west. His “Holy Roman Empire” shrank rapidly after his death, but it remained a major force in Europe into the Reformation. Although centered in modern Germany, its influence spread much wider.

Einhard, who wrote this biography, was a nobleman and a diplomat and adviser in Charlemagne’s service for over twenty-three years. In fact, the two were personal friends. This makes his report an invaluable source of firsthand information about the Emperor, but also alerts us to watch for personal bias.

Charlemagne presents Christians today with a dilemma. On the one hand, we ask, aren’t Charlemagne’s bloodthirsty ways of spreading the church completely alien to the gospel of Christ? On the other, we wonder would the church have survived if not for him?

Despite being anointed by the Pope as a child, Charlemagne was seen as the unlikeliest ruler. Before he died, though, he was the emperor of Western Europe. Trace the man back to his roots with this eye-opening video.

: 00:00 Determining Charlemagne's Origins

03:06 The Frankish Kingdom Expands

06:29 Charlemagne's Unlikely Ascent to Power

12:03 Charlemagne Vies for Higher Status

16:04 A Pivotal Moment in Charlemagne's Career

20:13 The Many Wars Waged by Charlemagne

23:56 Saxon Resistance Emerges

26:14 Charlemagne's Defeat in Spain

Religious reform of Charlemagne Religious reform of Charlemagne

Cultural revival

Another notable feature of Charlemagne’s reign was his recognition of the implications for his political and religious programs of the cultural renewal unfolding across much of the Christian West during the 8th century. He and his government patronized a variety of activities that together produced a cultural renovatio (Latin: “renewal” or “restoration”), later called the Carolingian Renaissance. The renewal was given impetus and shape by a circle of educated men—mostly clerics from Italy, Spain, Ireland, and England—to whom Charlemagne gave prominent place in his court in the 780s and 790s; the most influential member of this group was the Anglo-Saxon cleric Alcuin. The interactions among members of the circle, in which the king and a growing number of young Frankish aristocrats often participated, prompted Charlemagne to issue a series of orders defining the objectives of royal cultural policy. Its prime goal was to be the extension and improvement of Latin literacy, an end viewed as essential to enabling administrators and pastors to understand and discharge their responsibilities effectively. Achieving this goal required the expansion of the educational system and the production of books containing the essentials of Christian Latin culture.

The court circle played a key role in producing manuals required to teach Latin, to expound the basic tenets of the faith, and to perform the liturgy correctly. It also helped create a royal library containing works that permitted a deeper exploration of Latin learning and the Christian faith. A royal scriptorium was established, which played an important role in propagating the Carolingian minuscule, a new writing system that made copying and reading easier, and in experimenting with art forms useful in decorating books and in transmitting visually the message contained in them. Members of the court circle composed poetry, historiography, biblical exegesis, theological tracts, and epistles—works that exemplified advanced levels of intellectual activity and linguistic expertise. Their efforts prompted Alcuin to boast that a “new Athens” was in the making in Francia. The new Athens came to be identified with Aachen, from about 794 Charlemagne’s favourite royal residence. Aachen was the centre of a major building program that included the Palatine Chapel, a masterpiece of Carolingian architecture that served as Charlemagne’s imperial church.

Royal directives and the cultural models provided by the court circle were quickly imitated in cultural centres across the kingdom where signs of renewal were already emerging. Bishops and abbots, sometimes with the support of lay magnates, sought to revitalize existing episcopal and monastic schools and to found new ones, and measures were taken to increase the number of students. Some schoolmasters went beyond elementary Latin education to develop curricula and compile textbooks in the traditional seven liberal arts. The number of scriptoria and their productive capacity increased dramatically. And the number and size of libraries expanded, especially in monasteries, where book collections often included Classical texts whose only surviving copies were made for those libraries. Although the full fruits of the Carolingian Renaissance emerged only after Charlemagne’s death, the consequences of his cultural program appeared already during his lifetime in improved competence in Latin, expanded use of written documents in civil and ecclesiastical administration, advanced levels of discourse and stylistic versatility in formal literary productions, enriched liturgical usages, and variegated techniques and motifs employed in architecture and the visual arts.

Legacy

In January 814 Charlemagne fell ill with a fever after bathing in his beloved warm springs at Aachen; he died one week later. Writing in the 840s, the emperor’s grandson, the historian Nithard, avowed that at the end of his life the great king had “left all Europe filled with every goodness.” Modern historians have made apparent the exaggeration in that statement by calling attention to the inadequacies of Charlemagne’s political apparatus, the limitations of his military forces in the face of new threats from seafaring foes, the failure of his religious reforms to affect the great mass of Christians, the narrow traditionalism and clerical bias of his cultural program, and the oppressive features of his economic and social programs. Such critical attention of Charlemagne’s role, however, cannot efface the fact that his effort to adjust traditional Frankish ideas of leadership and the public good to new currents in society made a crucial difference in European history.

His renewal of the Roman Empire in the West provided the ideological foundation for a politically unified Europe, an idea that has inspired Europeans ever since—sometimes with unhappy consequences. His feats as a ruler, both real and imagined, served as a standard to which many generations of European rulers looked for guidance in defining and discharging their royal functions. His religious reforms solidified the organizational structures and the liturgical practices that eventually enfolded most of Europe into a single “Church.” His definition of the role of the secular authority in directing religious life laid the basis for the tension-filled interaction between temporal and spiritual authority that played a crucial role in shaping both political and religious institutions in later western European history.

His cultural renaissance provided the basic tools—schools, curricula, textbooks, libraries, and teaching techniques—upon which later cultural revivals would be based. The impetus he gave to the lord-vassal relationship and to the system of agriculture known as manorialism (in which peasants held land from a lord in exchange for dues and service) played a vital role in establishing the seignorial system (in which lords exercised political and economic power over a given territory and its population); the seignorial system in turn had the potential for imposing political and social order and for stimulating economic growth. Such accomplishments certainly justify the superlatives by which he was known in his own time: Carolus Magnus (“Charles the Great”) and Europae pater (“father of Europe”).

First phaseMiddle phaseFinal phaseReligious natureSee alsoReferencesSourcesSaxon Wars

@kennylong7281

(edited)